How does going to an aerobics class lead to joining a campaign to cement an American actor’s place in history?

Just ask Barbara Johnson Williams, a member of the Keuka College Class of 1963, who did just that. She says it began quite accidentally.

The Beginning

“In 2008, my husband, Richard, and I decided that visiting Poland would be our next vacation,” says Barbara, who transferred to American University in Beirut, Lebanon, after her sophomore year. She still considers herself a Keukonian, and has long been a Keuka College supporter, particularly of the Judith Oliver Brown ’63 Memorial Scholarship.

“One morning in my aerobics class, I met a woman who had an interesting accent,” says Barbara. “Walking out of class at the same time, I took the chance to introduce myself to that interesting accent.”

Upon learning her new friend was from Poland, Barbara told her that she and Richard were planning to visit her home country.

“She insisted that when we were ready to learn background materials for the upcoming trip, that I visit her home,” says Barbara. “I did, and in one of the 10 history books she gave me to read, there was a printed statement on the right-hand side of the page: ‘Black American Shakespearean tragedian Ira Aldridge is buried in the Evangelical cemetery of Łódź, Poland.’”

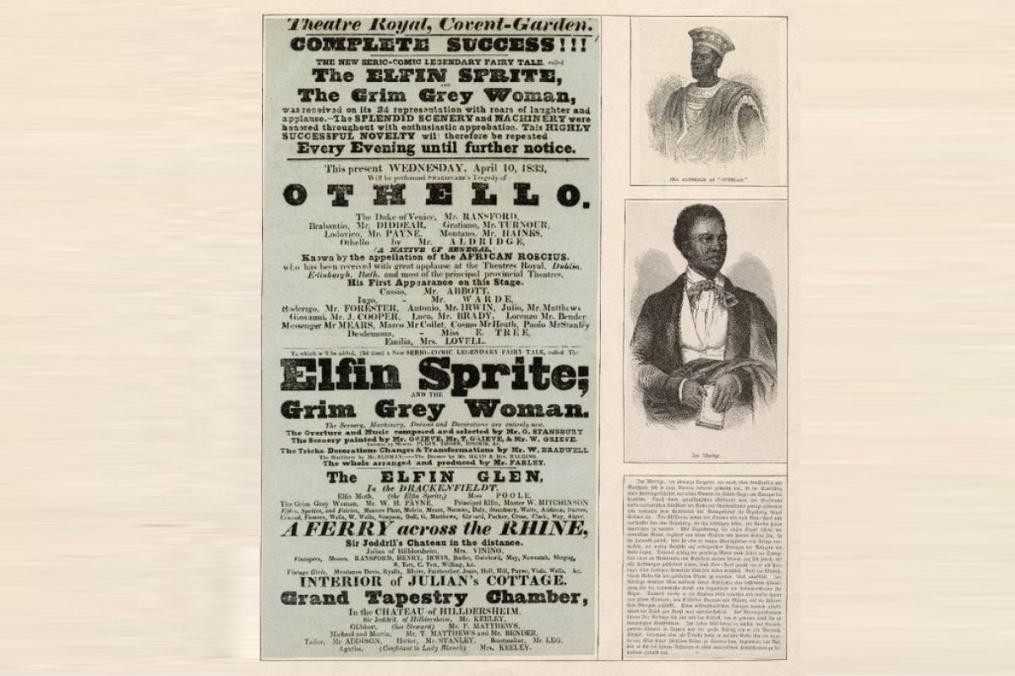

Ira Aldridge was a 19th-century African-American actor who became a renowned interpreter of Shakespearean tragedy on the European stage. He was the first African-American actor to achieve success on the international stage.

The Aldridge Connection

But until reading that statement in the book, the name “Ira Aldridge” didn’t mean much to Barbara. Then, she had a flashback to her days at Howard University.

“For three years, I had walked across the campus of Howard University, passing the Ira Aldridge Theatre, constructed in 1961,” says Barbara. “I arrived on campus the fall of 1963, but I had no connection to that name or building until 2008.”

Interested in learning more about his background, Barbara began researching the actor, and found his story intriguing. So, during her trip to Poland that same year, she wanted to visit Aldridge’s grave.

“During our bus tour, we could not make any changes to get to Łódź, but I vowed to Richard that we would return, and we did four years later, in October 2012,” she says. “I believed Ira’s story needed to be told, so I took it upon myself to do so. He was the epitome of a Shakespearean actor, so why is his name so often omitted from history?”

Barbara’s research turned up the answer: Because he was black, Aldridge was not allowed to perform on most U.S. stages in the mid-1800s.

Life Abroad

“He left the U.S. at age 18 for England, and never returned,” says Barbara. “So, people who named U.S. schools or theaters after him knew of him only after word filtered back over the years during his life in Europe, and after he died in Poland in 1867.”

Barbara discovered acting troupes, drama clubs, schools, and theaters across the U.S. named in honor of Aldridge. San Antonio, Texas, has a street—Ira Aldridge Place—named after the famed actor. In addition, Barbara discovered nearly a dozen plays, musicals, and a movie were written about Aldridge. One musical, “Born a Unicorn,” starred Ted Lange, perhaps best known for his role as Isaac Washington on the TV series The Love Boat.

Emigrating to England as a fellow actor’s valet, Aldridge was able to find more creative opportunities, albeit with significant challenges. In 1825, Aldridge had a starring role as Oroonoko in The Revolt of Surinam in the Coburg Theatre. His performance failed to launch a career for him on the London stage, and he faced racist rhetoric in the papers.

Undeterred, Aldridge spent years touring the United Kingdom, pushing social boundaries by playing the white title role in such Shakespearean works as Macbeth,The Merchant of Venice, King Lear, and Richard III. He would also portray the black antagonists Aaron and Othello—a role he would remain associated with until his death. And it was precisely these performances in countries throughout Europe that brought him international fame and recognition.

In 1858, when Aldridge preformed as Richard III in Kraków, Polish audiences had the first opportunity to see that play in the theater. His interpretation of the tragedy of Othello contributed to the emergence of the first Polish translation of the play. It was first staged in Warsaw, in 1862, with Aldridge in the title role.

Leaving a Legacy

While pleased to learn Aldridge had received the accolades Barbara thought he deserved, her research focus was a bit different.

“My focus was not as much on how well he was revered, received awards, or honored at the national level of so many European countries,” says Barbara. “I'm not a historian, or Shakespeare scholar, or even a general theater buff. My work delves with the legacies he left in the U.S. and England.”

And what a legacy it was.

Throughout the mid-1820s to 1860, Aldridge slowly forged a remarkable career. In 1852, he embarked on a series of international tours that would last until the end of his life. He performed for countless crowds in Prussia, Germany,Austria,Switzerland,Hungary, Poland, and Scotland, among others. In addition, Aldridge introduced Shakespeare to Serbian and Turkish cultures. He is also the only African-American actor to have a memorial plaque in his name installed in the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre at Stratford-upon-Avon.

And thanks in large part to Barbara’s efforts, another plaque was unveiled in 2014 in Łódź to honor Aldridge’s memory and legacy. The plaque is on the front of the former hotel and Paradyz Theatre, where the actor died unexpectedly on Aug. 7, 1867, during a rehearsal of Othello.